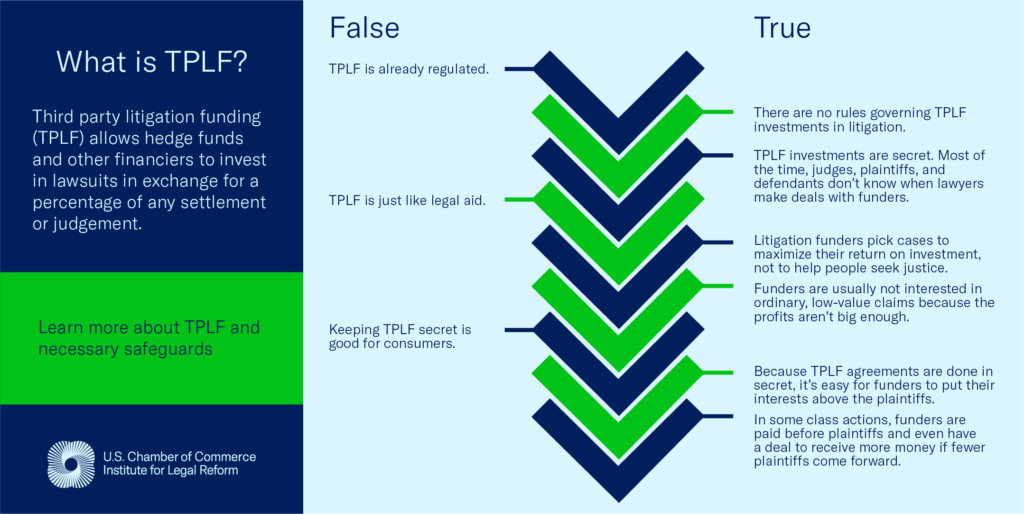

Third party litigation funding (TPLF) allows hedge funds and other financiers to invest in lawsuits in exchange for a percentage of any settlement or judgment. The practice started in Australia, expanded to Europe and the U.S., and is now spreading elsewhere. Without disclosure requirements and other commonsense safeguards, these funders may take over litigation and fuel unmeritorious lawsuits.

TPLF Glossary

Litigation Funders

Entities that advance money to plaintiffs or law firms to cover litigation or other costs on a non-recourse basis contingent on the outcome of the case. According to the Government Accountability Office, many are private institutions that specialize in TPLF, some are publicly traded, some are hedge funds and many receive capital from various sources such as sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and endowments. They are not parties to the lawsuit.

Litigation Funding Agreement

The contract that sets forth the terms of the funding arrangement. Generally, these documents are not required to be disclosed. Still, some courts and states have implemented disclosure requirements either through adopting a court rule or passing legislation (e.g., the Federal District of New Jersey, Northern District of California for class actions, Federal District of Delaware, and Wisconsin).

Disclosure

Typically done in one of two ways: in camera (i.e., disclosed only to the judge) or between the parties (i.e., disclosed to the opposing party). Disclosure allows the court and parties to know the identity of the litigation funder and may help determine whether the funders are exercising undue influence, violating any ethical rules, or whether conflicts of interest exist.

Non-recourse

This means that if no recovery is made from the dispute, the borrower is not obligated to repay the funder.

Portfolio Funding

Litigation funders finance multiple cases belonging to a lawyer or law firm, with the return on invested capital coming from the settlement or judgment of any individuals or group of cases. Portfolio funding allows the litigation funder to essentially bankroll all or a portion of a law firm’s case in exchange for a cut of any proceeds. This practice makes litigation funding less risky by allowing funders to spread their risk over multiple cases.

Champerty

An old English law doctrine that prohibits third parties from providing financial assistance to a claimant for a financial interest in the outcome of a dispute. While this doctrine is limited in some states, it does remain in multiple jurisdictions.

Maintenance

Prohibits a third party from “intermeddling” with another’s lawsuit. Like champerty, it has been limited in some states but remains in others.

FAQs

What Is Third Party Litigation Funding?

Third party litigation funding (TPLF) is the process where third party funders provide money to a plaintiff or plaintiff’s counsel in exchange for a cut of the proceeds resulting from the underlying litigation or settlement. They typically involve a funding agreement that contains the funder’s identity, investment amount, payment schedule, and whether the funder may exercise any strategic control over the litigation.

Litigation funding is typically divided into two main groups: consumer and commercial or investment. Consumer litigation funding arrangements generally involve a plaintiff seeking financial support from a funder for living or other expenses, usually related to tort or personal injury claims. Alternatively, investment or commercial litigation funding arrangements often involve large–scale tort and commercial cases and alternative dispute resolution proceedings. Moreover, investment /commercial funding arrangements may involve a single-case or multiple cases (i.e., portfolio funding).

Typically, these arrangements are non-recourse, meaning that if the plaintiff’s suit is unsuccessful, then the funder receives nothing.

Traditionally, the common law doctrines of maintenance and champerty prohibited non-parties from financing litigation, but recently some jurisdictions have relaxed these outright prohibitions.

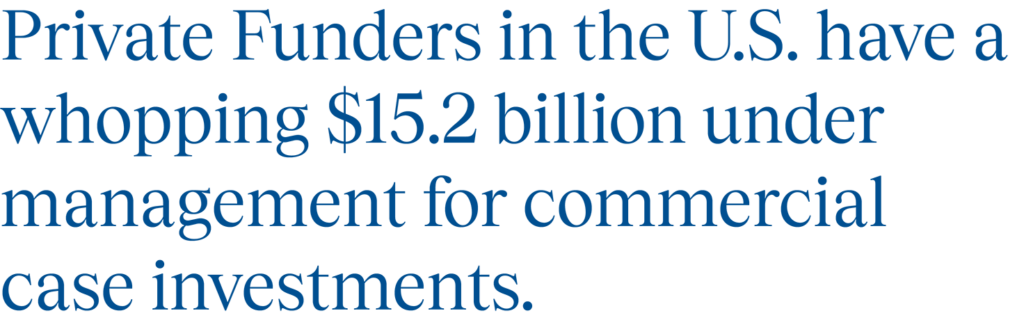

How Big is the Litigation Funding Industry?

It is difficult to tell the exact size of the litigation funding industry because very few jurisdictions require the disclosure of litigation funding agreements.

TPLF started around the mid-1990s in Australia and quickly spread across the globe, arriving in the United States about a decade later. In recent years, TPLF has experienced explosive growth and is now a multi-billion-dollar industry worldwide, with an estimated $15.2 billion in commercial litigation investments in the United States alone.

What’s the Problem with TPLF?

TPLF is problematic for a variety of reasons.

Allowing outsiders to secretly use courtrooms as a trading floor incentivizes the filing of non-meritorious litigation. Litigation is extremely expensive, and businesses seek to avoid it. Businesses often settle cases rather than engage in protracted and costly litigation, regardless of whether the claims are legitimate. Since TPLF lets plaintiffs off the hook for legal costs, there is little risk for them to advance non-meritorious claims.

When companies face higher litigation costs, they are often forced to raise prices for consumers. Furthermore, TPLF can corrupt the legal system by prioritizing profit over justice, putting the investment interests of funders ahead of the interests of others, including the plaintiffs themselves. In essence, TPLF can weaken the fairness and integrity of the legal system and negatively impact the economy.

TPLF allows funders to exercise undue control or influence over the litigation to the detriment of courts, defendants and plaintiffs. For example, in some TPLF agreements, there are provisions that allow funders to make strategic decisions like whether and when to settle, even if the plaintiff would rather proceed to trial. Unlike attorneys, funders do not owe a fiduciary duty to the plaintiffs and may not be acting in their best interest.

TPLF often contravenes the Model Rules of Professional Conduct, which are designed to ensure that lawyers act in the best interest of their clients. For example, rule 5.4 prohibits fee-splitting between a lawyer and a nonlawyer. Certain TPLF agreements violate Rule 5.4’s fee-splitting provision because funders are paid a percentage of the legal fees secured by the plaintiff’s attorney. Rule 5.4 also prohibits nonlawyers from having an ownership interest in law firms. Some litigation funders would like to abolish Rule 5.4 to acquire ownership interests in law firms to streamline funding.

Why is Mandatory Disclosure Important?

Disclosure is important because litigation funding agreements are generally kept secret. As a result, nobody knows what control or influence the funders have over the underlying litigation or attorneys. In most cases, knowing whether there is TPLF in any given case is impossible. Requiring the disclosure of TPLF agreements would bring to light many of the previously discussed issues and incentivize funders (and attorneys) to behave ethically.

How Does TPLF Work?

Litigation funders identify cases where there is likely to be a large award and arrange with law firms or plaintiffs to pay the litigation costs in exchange for a share of the outcome. Funders also engage in “portfolio funding,” in which they purchase a contingent interest in the outcome of a whole portfolio of lawsuits. The involvement of TPLF in litigation raises a host of ethical issues.

TPLF Takeaways

Funders Operate in the Shadows

Once a funder decides to finance a lawsuit, they will enter into a litigation funding agreement with the funded party, usually a law firm or plaintiffs’ lawyer. There is often no mandatory disclosure of these agreements. This means that judges, defendants, and even plaintiffs (particularly in class actions) may not know that a hidden third party has a stake in—and an expectation to profit from—the case in front of them.

Third Party Litigation Funding is a Risk to National Security

ILR has been warning about the need for transparency because everyone involved in a lawsuit should know who is funding it and calling the shots in the litigation and where exactly that money is coming from. In 2022, ILR released research that pointed out how the lack of safeguards around TPLF could have serious national security implications. There’s nothing stopping adversarial governments from using litigation funding to pour money into cases against American companies, including defense and other sensitive industries, in order to tie them down in litigation, make them spend money, or access their intellectual property.

Headlines show that ILR is right to have concerns. Bloomberg Law recently published a bombshell article exposing how an investment firm established by sanctioned Russian billionaires with ties to Vladimir Putin has funded lawsuits in the U.S. and UK to evade international sanctions. Last year, PurpleVine IP, a Chinese third-party litigation investment firm, financed multiple intellectual property lawsuits in U.S. courts against Samsung and a subsidiary. The only reason we are aware of this funding is because the Chief Judge of the U.S. district court in Delaware, where one of the lawsuits was filed, has a standing order requiring disclosure of all litigation funding in his courtroom. The plaintiff in that case has since acknowledged that PurpleVine is funding three similar cases in federal court in Texas.

The increasing use of third party funding in U.S. patent lawsuits poses a threat to national security, too. This practice, which now plays a role in about 30% of the country’s infringement cases, hides the identities of those funding and controlling these lawsuits. This secrecy could allow foreign adversaries to benefit from influencing the American legal system.

For instance, in the case between Intel and VLSI Technology—a company supported by a hedge fund linked to Abu Dhabi and opposed to disclosing its litigation funding sources— the dispute was over claims that Intel’s microprocessors violated VLSI’s patents. This legal clash not only takes away resources from Intel’s crucial work in semiconductor innovation and production, vital for the U.S. economy and military technology, but also raises worries about undisclosed foreign participation in lawsuits that could harm U.S. interests.

The lack of transparency in third party litigation funding, especially when companies like VLSI refuse to reveal who is backing them, highlights the need for measures to ensure the public knows who is using our courts.

In December 2022, 14 state attorneys general (AGs) sent a letter to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), asking U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland and other top officials about the steps being taken to protect the country against potential national security threats posed by TPLF. In January 2023, Senator John Kennedy sent a similar letter. And in November 2023, Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Rick Scott (R-FL) wrote to the chief judges of Florida’s federal district courts urging those courts to adopt disclosure requirements for foreign-sourced TPLF.

Funders May Take Control of Litigation

If a third party has a financial stake in a lawsuit, it will naturally want to control or influence the lawsuit, sometimes to the detriment of the actual party in interest. Funders often design funding agreements to maximize their chances of success and their profits. They will want to influence the strategic decisions of the funded party in litigation, including fundamental issues such as selecting a lawyer, choosing an expert witness, accepting or rejecting a settlement agreement. Furthermore, when lawyers depend on funders to get paid or count on their financing in future cases, they may face pressure to let the funders have their way. This creates a power dynamic that can undermine the interests of the plaintiffs in the case and the proper working of the courts.

The legal battle between Sysco and Burford Capital highlights this issue. Sysco accused Burford Capital, its litigation financier, of blocking reasonable settlement offers in its antitrust case, effectively trapping Sysco in a lawsuit it wished to settle. Burford Capital then attempted to replace Sysco as the main party in the lawsuit. However, a court ruling has rejected Burford’s attempt to take Sysco’s place. It is crucial to establish transparency and oversight of TPLF so that funders cannot hold plaintiffs hostage in their litigation.

Funders Are Often Paid Before Plaintiffs

Funding agreements also lay out how exactly the funder will be paid. In many known instances, when the plaintiff wins a funded case, the funder will first take its cut of the winnings before the plaintiff is paid—often 20-40% of the proceeds of the case, or even more. These arrangements can leave plaintiffs (particularly in class actions) with little or no money, especially if the lawyers also take a contingency or large winning fee.

Litigation Funding Puts Investors Ahead of Plaintiffs

Third party funders generally don’t have to abide by any ethical or fiduciary rules. Their priority is their financial investment, not the best interests of the plaintiffs. In fact, in some funded class actions, the funding agreements are structured so that the fewer people who claim their award, the more money the funder gets.

PBS aired a gripping, true-life story of a legal system run amok. “Mr. Bates vs. The Post Office,” which first aired on Britain’s ITV, shows how a group of British postmasters were doubly abused—first by false accusations of theft and accounting fraud that left many in financial ruin or prison; second, by a lawsuit where litigation funders and plaintiffs’ lawyers took more than 80 percent of the settlement before the postmasters saw one penny. While the specifics of the postmasters’ plight are unique, the abuses in this real-life example of TPLF show how hedge funds and other financiers secretly invest in and control lawsuits in exchange for a high percentage of the settlement to the detriment of claimants.

There is Little to No Regulation and No Uniform Requirement for Disclosure

Litigation funding, at a minimum, should be disclosed and subject to fair and proportionate safeguards like other financial and legal professions to prevent litigation abuse and ensure adequate compensation to plaintiffs.

A survey released by ILR shows that 69 percent of voters, including strong majorities of Republicans, Democrats, and Independents, support requiring the disclosure of TPLF. The survey also shows that 82 percent of voters across the political spectrum oppose allowing foreign governments to invest in U.S. lawsuits against American companies. A recent ILR report, ILR Briefly: A New Threat: The National Security Risk of Third Party Litigation Funding, found:

- There is a growing concern that a large volume of foreign-sourced money may be pouring into U.S. civil litigation against U.S. companies and industries (including those in defense and other highly sensitive sectors).

- A foreign government could fund litigation to advance its strategic interests against the U.S.

- Though the U.S. government has taken action to limit foreign access to U.S. technology, there is no measure currently in place to prevent foreign adversaries from using TPLF to circumvent existing safeguards.

You can read the details of the survey in our blog New Poll: Voters Want TPLF Disclosure.

Would Self-Regulation Suffice?

In some countries, like the UK, funders claim to abide by self-regulation through voluntary codes of conduct. Unfortunately, the self-regulation of TPLF is fraught with numerous problems that undermine its effectiveness. According to a report by Fair Civil Justice, self-regulation lacks enforceable standards and sanctions, allowing funders to operate without accountability or consequences for unethical practices. The voluntary nature of such regulation means that many funders can simply opt out, leaving a significant portion of the industry unregulated. Additionally, self-regulation often fails to address conflicts of interest and the potential for funders to exert undue influence over litigation, compromising the integrity of the legal process. Self-regulation of TPLF falls fall short in protecting the interests of plaintiffs and the justice system as a whole. Mandatory oversight and safeguards of the funding industry are needed.

TPLF Research

The Institute for Legal Reform’s research program is cutting-edge. We examine the most pressing civil justice issues facing legal systems across the world. We work with some of the world’s foremost legal experts to offer insights and potential solutions for a more just legal system.

Litigation funders perpetuate the myth that their industry is a benign force that enhances access to justice, suggesting there’s “nothing to see here” when it comes to third-party litigation funding (TPLF). However, this narrative is far from the truth, as this research reveals several concerning patterns:

- Control Over Litigation: Funders often exercise significant control over litigation, contrary to their claims of being passive investors. This control threatens the professional independence of lawyers, and disrupts the loyalty that counsel owe to their clients.

- Foreign Influence and National Security Risks: TPLF poses national security risks. There are concerns about foreign adversaries using TPLF to undermine the interests of the U.S. and allied countries, gain access to sensitive information, or evade sanctions.

- Financial Impact on Litigants: TPLF often results in significant portions of settlements and judgments being siphoned off by funders, leaving actual claimants with greatly reduced recoveries after attorneys’ fees are also deducted.

The research also shows that there is increasing concern from policymakers about the injurious effects of TPLF on claimants, businesses, and civil justice systems in general. Indeed, the paper documents numerous examples of policymakers calling for or taking action to implement safeguards around TPLF in courts, in the states, on Capitol Hill and overseas. The report’s major takeaway is this: TPLF poses significant challenges to the proper functioning of civil justice, and after years of advocacy by ILR and others, policymakers are increasingly confronting the problem.

Read Grim Realities: Debunking Myths in Third-Party Litigation Funding to learn more.

The American Bar Association’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct provide critical guidance for attorneys and protection for clients, the legal profession, and the public at large. One of these rules, Rule 5.4, safeguards lawyer independence by prohibiting nonlawyers from owning law firms or splitting fees with attorneys.

However, there is a movement that seeks to end or limit restrictions on nonlawyer ownership of and financial investment in law firms. Some argue that eliminating or modifying Rule 5.4 will increase access to legal representation. But those who stand to gain the most from these potential changes are not potential clients in need of legal services. Changes to Rule 5.4 would accommodate the questionable use of third party litigation funding (TPLF) and benefit the firms that engage in it.

Read Selling Out: The Dangers of Allowing Nonattorney Investment in Law Firms to learn more.

The lack of safeguards in third party litigation funding (TPLF) provides a clear path for foreign adversaries to undermine U.S. national economic and security interests through the infiltration of the American litigation system.

The research makes the case that few barriers exist to prevent a person or entity acting on behalf of a foreign adversary like China or Russia from covertly financing litigation against U.S. companies. Their incentives to do so are clear: By fostering strategic litigation against targeted U.S. companies or entire sectors, a foreign adversary could realize a range of objectives, whether advantaging their own competing industries, accessing sensitive information through the litigation process, or degrading the U.S. economy and weakening its national security. And through TPLF, an adversary can pursue these goals with little risk of their involvement ever coming to light.

ILR’s research offers a deep dive into TPLF’s troubling implications for national security and suggests various legislative and executive solutions to address this intolerable weak point in America’s national security architecture.

Read ILR Briefly: A New Threat: The National Security Risk of Third Party Litigation Funding to learn more.

This ILR research report looks at the explosive growth of the TPLF industry, how the industry is fueling abusive litigation, how the few TPLF agreements that have been made public reveal ethical issues within the practice, and how lawmakers can handle TPLF reform.

Some solutions from the research include:

- TPLF agreements must be disclosed to all parties in litigation to minimize conflicts of interest and ensure plaintiffs retain control of their case

- Fee-sharing agreements between lawyers and nonlawyers should be banned (as several bar associations have already done) to preserve the independent professional judgment of attorneys.

- TPLF should not be permitted in the class action context because funding creates a potential obstacle to class counsel and named plaintiffs satisfying their fiduciary duties to the class

Read Selling More Lawsuits, Buying More Trouble to learn more.

The federal False Claims Act (FCA) is the principal statutory mechanism for combating fraud against the U.S. government—but it seems the third party litigation funding (TPLF) industry is also trying to make it a new source of revenue. They specifically target the qui tam provision of the FCA, which allows private citizens (relators) to bring lawsuits on behalf of the government alleging violations of the Act in return for a certain percentage of any resulting recoveries, with the rest going to the government. The vast majority of FCA actions in any given year are brought by qui tam relators. In each action, the government may decide whether or not to take over the case (with the relator getting paid either way), or to move for dismissal if it doesn’t think the case has merit.

The paper discusses the DOJ’s announcement that they would take steps to remedy information gaps in the False Claims Act.

Read ILR Briefly: Third Party Litigation Funding In Qui Tam False Claims Act Cases to learn more.

This ILR survey report finds that European consumers do not want lawsuit finance companies to invest in civil litigation without oversight. They strongly support a variety of proposed safeguards to keep third party litigation funding (TPLF) in check.

TPLF involves companies making often-secret deals with lawyers to fund lawsuits in exchange for a cut of any judgment or settlement. Currently, those companies operate under a near-total lack of regulation and transparency in the EU and around the world.

83% of those surveyed support the introduction of safeguards to ensure cases funded by TPLF operate in consumers’ best interests, and between 66 and 79 percent support a range of specific proposed safeguards. Among the top polled safeguards are proposals that:

- Funders should have a fiduciary duty to put the best interests of claimants over their own investment interests (79%);

- Funders should be legally required to see a case through until the end, without the ability to withdraw their funding before a case is concluded (78%); and

- Funding agreements should be subject to an independent review to ensure they are not written unfairly in favor of the funders (78%).

Read Consumer Attitudes to Third Party Litigation Funding and its Potential Regulation in the EU to learn more.

TPLF Blogs

Want to learn more about third party litigation funding? Check out some of our blogs.

TPLF Podcasts

ILR’s award-winning podcast has episodes on third party litigation funding.