Have you ever wondered how to join a class action lawsuit? It might seem like a convenient avenue to seek recourse for a harm you experienced. In theory, class actions allow groups of individuals who have been wronged by a company or organization to band together and pursue justice in a single, consolidated case. However, in practice, class actions often fail to deliver on their promise of efficiency and fairness. We’ll explore the problems with class action lawsuits and why they continue to be in dire need of reform. After reading about the troublesome U.S. class action lawsuit system, you likely won’t be wondering how to join a class action lawsuit anymore.

One of the biggest issues with joining a class action is the proportion of earnings awarded to class members versus plaintiffs’ attorneys. The odds are low that you know someone who has received meaningful compensation as a class member in a class action lawsuit. Instead, you have likely heard stories of members who join class action lawsuits and receive nominal or token awards, or even coupons, as part of a class action settlement while plaintiffs’ attorneys earn millions. According to a 2015 Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) study, the average award to consumers is only $32, while plaintiffs’ lawyers take home nearly $1 million on average.

As highlighted in ILR’s research, Unfair Inefficient, Unpredictable: Class Action Flaws and the Road to Reform, “one study of class action settlements from 2019-2020 found that “more than half of [class] settlement[s] on average went to attorneys or others who were not class members.” Here are some examples of cases that demonstrate the disparity between individual class member payments and plaintiffs’ lawyer earnings:

- The Subway Footlong Sandwich Case: In this case, a group of plaintiffs sued Subway for allegedly selling “footlong” sandwiches that were shorter than advertised. The case was settled for $525,000, but the lawyers who represented the class members earned $525,000 in fees, which was equal to the entire settlement amount. The class members received only coupons for free sandwiches.

- The Target Data Breach Case: In this case, a class of plaintiffs sued Target for allegedly failing to protect their personal information from a data breach. The case was settled for $10 million, but the lawyers who represented the class members earned $6.75 million in fees, while the class members received only small payouts or free credit monitoring services.

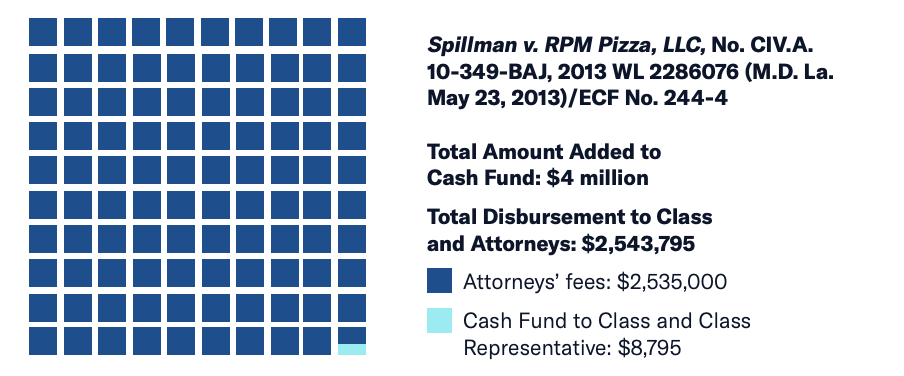

- The Pizza Shop Robocaller Case: In this case, a pizza company allegedly violated the Telephone Consumer Protection Act by sending unsolicited cell phone messages advertising promotions. Only 253 claimants elected to receive a cash payment, resulting in a total cash disbursement of $8,795 to the class. By contrast, attorneys received $2,535,000 in fees and costs.

Source: Unfair Inefficient, Unpredictable: Class Action Flaws and the Road to Reform

- The Keurig Class Action Lawsuit: Smith v. Keurig was a class action lawsuit about the labeling and advertising of K Cup® single serving coffee pods labeled as recyclable. Class members in the Keurig class action lawsuit were only reimbursed $3.50 per 100 pods, up to $36 maximum per household, while the plaintiffs’ lawyers were eligible for $3 million in attorneys’ fees.

The potential for punitive damages, or damages intended to punish a defendant for particularly egregious behavior and deter similar conduct in the future, is an additional area of concern. Punitive damages can be dangerous in class action lawsuits because they can result in large monetary awards that are disproportionate to the actual harm suffered by class members and oftentimes are not distributed to class members in a meaningful way–instead primarily benefiting the lawyers who brought the case.

For a class action seeking monetary damages, class members do not choose to join class action lawsuits, or “opt-in”, which can be problematic. This means that in many class action lawsuits, class members must take action to “opt-out” by providing notice to the court. However, some class actions are so large that it may be nearly impossible to notify all potential class members, as described in our recent blog post, What is an Opt-Out Class Action Lawsuit? As an unknowing class member, you may lose the opportunity to collect your award, and you may forfeit your ability to independently file a lawsuit against the defendant who caused harm.

Another driver behind questionable behavior in class action lawsuits is the use of third party litigation funding (TPLF). TPLF allows hedge funds and financiers to secretly invest in lawsuits in return for a portion of the award or settlement. There is very little transparency; often the judge, defendants and even the class members don’t know who is secretly funding or controlling the lawsuits.

A recent Wall Street Journal editorial about litigation funder Burford Capital shined a light on the hidden dangers of the secretive TPLF industry. Although Burford Capital has claimed their clients are “free to run their litigations as they see fit,” a now-settled lawsuit against the funder suggested otherwise.

Can We Fix the Class Action Lawsuit System?

Class actions are meant to provide access to justice to those who have experienced harm, but unfortunately, class actions most often benefit plaintiffs’ lawyers with lucrative paydays, while frequently providing only minimal or token compensation to class members.

Reforming the class action system is a complex endeavor that requires a balance between protecting the rights of class members, ensuring access to justice, and preventing abuse of the system by plaintiffs’ lawyers. A 2021 decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez was a step in the right direction. The decision said that for someone to be allowed to sue, they need to have experienced real harm, not just a vague problem. According to ILR’s research, TransUnion and Concrete Harm: One Year Later, the Supreme Court’s clarification about needing real harm will make it tougher for lawyers to get approval to represent the whole group in court. This means that if you join a class action lawsuit after experiencing real harm, you are more likely to receive just compensation than if a class is muddied with members who never experienced harm.

Reining in third party litigation funding is another way to reform the class action system. However, as it stands, there are few transparency requirements for this secretive industry. This is a problem because there is no way to tell if lawyers who are supposed to be representing you, the class member, are favoring the funders in critical decisions or reducing your recovery to pay these funders. Various state courts have started stepping up to implement policies that protect consumers. Northern California, New Jersey, and Delaware courts require some type of transparency in funding agreements. And during the 2023 state legislative session, Montana enacted a robust law that will bring much-needed transparency to its courts. The law requires disclosure of litigation agreements, funders to register with the secretary of state, makes funders jointly liable for costs, and caps the amount funders can get from settlements or awards at 25 percent. More states should take notice and implement similar protections.

It is important to hold those who commit wrongdoing accountable, but under the U.S. class action system, class members rarely see a dime. Before joining a class action, it may be in your best interest to consider pursuing other avenues of justice.